Economic Composition, Local Tech Scenes, & Opportunities for Community Banks

Small Cities Weekly | 12.05.2025

I send out a brief weekly post of thoughts, links, and research about the intersection of entrepreneurship, investing, economic development, and small cities. I’d love to hear from you if you have any thoughts, questions, disagreements, or things to add. Please forward this on to people you think might enjoy reading it.

Economic Composition

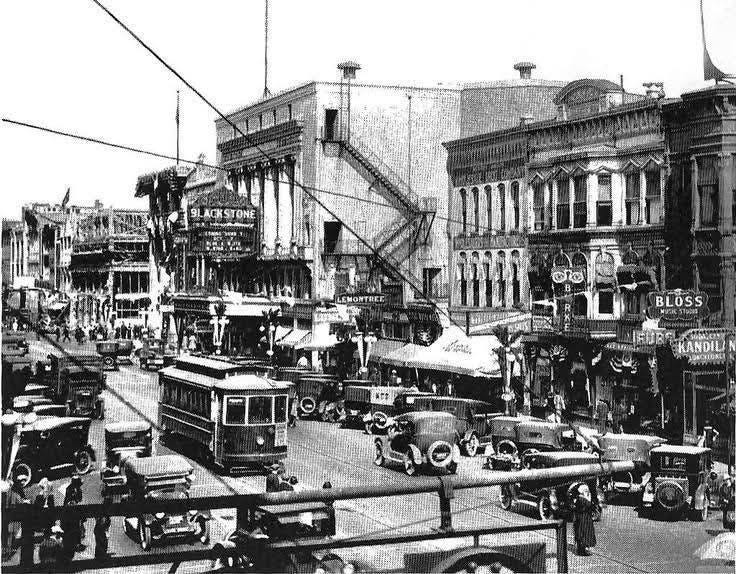

I spend a lot of time looking at old photos of South Bend and reading old newspaper clippings about life here. It’s an odd feeling to do so. I read the names of streets I know and drive, see buildings that still stand today, and learn about companies and people who today are known for what was named after them, not what they made their name doing. It feels like an alternative world taking place on the same city grid.

The early 1900s into the 1920s are an especially hard time to imagine for me. In the 50 years leading up to 1930, the population had exploded from 13,280 to 104,193. To give context, in the last 50 years, it’s gone from approximately 110,000 to 104,000. So population-wise, we are at a very similar scale. Trend-wise, we sit in a very different place.

In my quest to better wrap my arms around this history, I started to wonder what overall employment looked like. I knew Studebaker dominated the scene, but that’s kind of like knowing today that the University of Notre Dame is in South Bend. It’s true, but a limited view. With help from the local history museum, I tried to put together a list of the county’s top 10 employers at the time. The numbers and rankings aren’t perfect, but the broad outline is clear: with the lone exception of the local school corporation, almost all of the county’s major employers in the 1920s were locally founded private companies:

Studebaker Automobile Corporation

Oliver Farm Equipment Corporation

Bendix Corporation

Mishawaka Rubber Company/Ball-Band Rubber Corporation

South Bend Community School Corporation

O’Brien Paint and Varnish Company

South Bend Watch Company

South Bend Bait Company

Wheelabrator

Dodge Manufacturing Corporation

The economic story of the place was written largely through firms built here.

The same list today is vastly different. In the county today - as in nearly every small city I’ve visited - the top employers are hospitals, universities, school systems, governments, and a few industrial operations whose headquarters sit elsewhere. There are maybe one to two locally-owned enterprises, but they are the exception not the rule.

The institutions that now dominate our local employment have held the region together through decades of change. They’ve been the stability that have kept our population and economy from collapsing over the past 50 years. None of them asked to become the center of the employer list; the world shifted and they’ve taken the responsibility seriously.

But institutions aren’t immune to change either. Healthcare, higher ed, and local government are all in more volatile times than any of them have seen in years, maybe decades. And even if that volatility doesn’t spell crisis, it certainly seems probable that the next decade won’t look like the last.

This is where the old photos and newspaper clippings keep tugging at me. That era was another volatile time. But that volatility was borne by and concentrated in a different type of actor. The decade that ensued led to systemic changes that still shapes economies like ours today.

We face a different concentration today, but a concentration nonetheless. The similarities and the contrasts between then and now highlight something that maybe we should consider more primary to our economic development goals: an economy is healthier and more resilient when institutions and locally rooted companies each carry part of the load. Diversification of the local economy means that change in any one direction doesn’t tilt the whole system. While I doubt many disagree with this sentiment, it also seems to not be a stated goal. Growth and investment in the private economy is always welcome; but a steady state of economic composition is not usually part of the conversation.

We’re not in balance right now. Our employer composition has drifted far toward the institutional side, and those institutions are themselves entering a period of adjustment. That combination doesn’t mean the 2030s are going to rhyme with the 1930s, but it is a signal worth paying attention to.

The question I keep circling around is: What would it take to work our way intentionally toward an employer mix where institutions and locally rooted companies are in a mutual feedback loop that strengthen each other, rather than replace each other?

I hope 100 years from now that our community is somewhat unrecognizable from what it is today. It’s hard to believe in progress if you don’t accept that fate. But I do hope that there are some things that are the same - including feeling like we’ve built a local economy that responds well to the inevitable volatility it will face.

Links

You can find links from this and all previous editions here.

Why local tech scenes have changed, Alex Danco, It’s Time to Build (a16z)

Between these two forces - AI pulling people back into San Francisco (and Bay-Area headquartered companies, in the case that they have local offices) and AI making solo building a much more attractive proposition - there is now a much more difficult adverse selection problem in local tech scenes. There are just fewer A-players available to hire anymore.

As a result, in my observation anyway, the composition and the purpose of local tech scenes has changed pretty dramatically since a decade ago.

The Resilience Spread: How Climate Change Is Reshaping Regional Economies, First Street

Yet direct damages are only part of the story; these events have also triggered business interruptions, supply-chain breakdowns, and lost productivity. Altogether, physical climate risk has cost the global economy on average 0.2% of its gross domestic product (GDP) annually over the last decade, amounting to more than $203 billion in losses every year (Ritchie et al. 2022).

These losses have sweeping consequences for municipalities and global financial institutions, prompting an in-depth examination of how geography is impacting investments in an era of elevated climate risk. Many of these natural disaster losses can be traced back to impacts on urban centers, the same places that drive global growth, innovation, and investment.

Neighborhood Networks: A threat and an opportunity for community banks, Alex Johnson, FinTech Takes

Bilt is a national company, but its neighborhood benefits coverage is concentrated in big cities like New York, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Atlanta, Miami, and Los Angeles. Block will eventually roll out its neighborhood network nationally, but for now, it’s only available in Portland and Charlotte. The fly-over states and small towns that community banks specialize in serving won’t see these products anytime soon.

And even when they do, Bilt and Block, for all their aspirational messaging, are still large companies with demanding investors. At the end of the day, they will always prioritize commerce over community.

—

Imagine a neighborhood network that enables a local office supply store to offer a 40% discount in July to local school teachers to help them buy supplies. Or a neighborhood network that gives customers the option to round up their purchases to donate to the local food bank or to scholarships for underprivileged students

In short, imagine a neighborhood network built by a community bank.

You can reach me at dustin@invanti.co if you want to chat more about the small city segment!