Entrepreneurship Rates, Kalamazoo Housing, & Not Built for This

Small Cities Weekly | 08.23.2024

As part of the work we are doing on the Small City Segment, we send out a brief weekly post of thoughts, links, and research in progress that reflect the week’s work. I’d love to hear from you if you have any thoughts, questions, disagreements, or things to add. Please forward this on to people you think might enjoy reading it.

Entrepreneurship Rates

In my original post on the Small City Segment, I wrote:

The data show that entrepreneurship rates are more likely to be lower in these cities. 71% of them are in states with opportunity entrepreneurship rates (percent of new entrepreneurs who created a business by choice instead of necessity) below the national average. There just aren’t as many people starting things…

This number came from looking at research that the Kauffman Foundation has done on entrepreneurship rates in the US.

I thought it might be interesting to take what is mostly discussed in the form of rates and show what it really means on the scale of a small city, a collection of small cities, and a state. To get started, a few definitions that help with the assumptions. First are definitions lifted directly from the Kauffman research:

Entrepreneurship Rate: Percent of population that starts a new business

This indicator captures all new business owners, including those who own incorporated or unincorporated businesses, and those who are employers or non-employers

Opportunity Entrepreneurship Rate: Percent of new entrepreneurs who created a business by choice instead of necessity

The percent of the total number of new entrepreneurs who were not unemployed and not looking for a job as they started the new business. This distinction is useful because it offers some insight into the influence of economic conditions on overall business creation

Opportunity entrepreneurship rate still does not specify between types of businesses - restaurants, software, manufacturing, landscaping, etc. Since it seems to be the most common focus of economic development entrepreneurship agendas, let’s create another variable that reflects the rate of people starting “VC-backable” companies. It’s hard to find data on this rate, but I think we can make some assumptions that pass the gut test when all is said and done.

VC-Backable Entrepreneurship Rate: Percent of opportunity entrepreneurs that create businesses that are appropriate for venture capital financing

Pulling some data from the Census Bureau, Kauffman, and making an assumption about the VC-Backable Entrepreneurship Rate (start with 1% as the national average), we can get a sense of what these rates mean for a city like South Bend.

You’ll notice here that Indiana’s entrepreneurship rates are lower than the national rates. If we apply that same dynamic to our assumptions about the VC-Backable Rate, you can see that we are talking very small numbers here. Even at national rates, you’d only expect on the order of ten VC-Backable companies to be started per year. Add in the depressed rates in Indiana and that number is cut in more than half. It’s no wonder that funds, angel groups, accelerators, and incubators have a hard time sourcing deal flow!

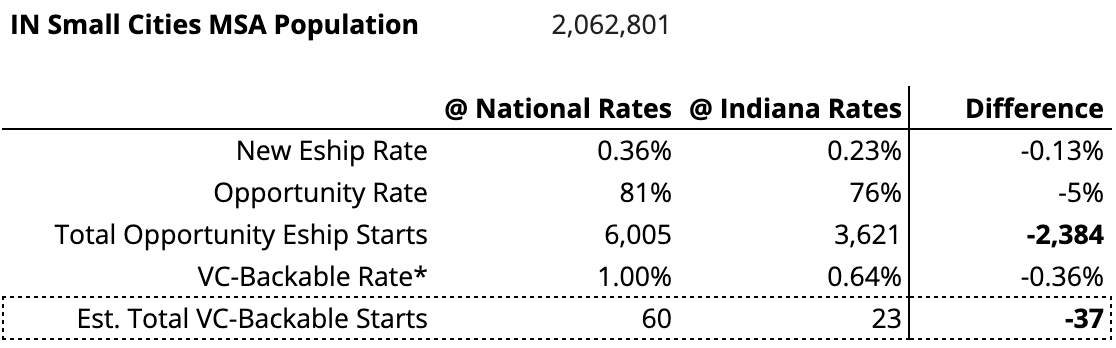

But this doesn’t just apply to the city level. What if we take all cities in Indiana between 100k and 500k people?

Even at the national rate, we haven’t hit 100 VC-Backable starts per year yet. Now I could be wildly off on my assumption of what the VC-Backable rate is, but even if you said the national rate was 5%, you’re lucky to hit 100 per year across these nine cities when you account for the depressed Indiana rates.

Just for completeness, here are what the numbers look like for the entire state of Indiana.

What stands out to me is the order of magnitude that we are talking about when we discuss the VC-backed, technology startup part of the economic development strategy. I’m all for this being a part of the equation - I think it is an important one. But in terms of absolute numbers, city-based, regional-based, and even state-based investment strategies have to wrestle with the magnitude of the deal flow that’s available. And remember - these are start rates, not success rates.

One question to ponder is how we get overall rates in these cities and the states they reside in closer to the national average. Even without worrying about the VC-backable rate, getting the overall entrepreneurship rate and the opportunity entrepreneurship rate up could have drastic results on economic growth, jobs, and dynamism.

I’m not against the VC model or technology startups (hopefully obviously!). And I fully understand that magnitude of success matters a lot - the power law can take small numbers and turn them into large impacts. But, if we are going to talk seriously about those strategies, I think it’s also necessary to be honest about the data. As in all things, our population size in small cities create dynamics that make us different than larger urban cities or the US as a whole. We need good answers as to how our strategies reflect that reality.

Links

You can find links from this and all previous editions here.

What Kalamazoo (Yes, Kalamazoo) Reveals About the Nation’s Housing Crisis, Conor Dougherty, NYTimes

I spent most of my time in Kalamazoo County, a region of 261,000 people in the southwest part of the state. It’s a good place to see how all of America, not just coastal cities, got into a housing crunch, and offers a look at some of the efforts to get out of it.

…

“Sucks but not homeless” is a pretty good summation of the ordinary pain the housing crisis has caused. It sucks to feel that you can’t afford to do anything fun. It sucks to live with family when you want your own apartment. It sucks to leave a high-cost city where you began your career because you can’t afford to buy there. It also sucks when people from high-cost cities flee to your low-cost city.

For all its housing price inflation, Kalamazoo is still so much cheaper than other parts of the country that it was recently named one of America’s most affordable cities for professionals. A darker way of putting it is that Kalamazoo is the final stop in the housing crisis. And that’s the problem with being a place where people move to feel richer: Those who get priced out have no place left to go.

Richest Hill, Nora Saks, Montana Public Radio

Butte Montana is famous. It was at one time the biggest city between Chicago and San Francisco. It’s in the heart of the Rocky Mountains, and sits at the headwaters of the mighty Columbia River, which flows all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

Butte boomed and thrived for almost a century because of one thing: copper.

Butte’s massive copper deposit was key to America’s success. The “Richest Hill on Earth” literally electrified the nation, and made the brass in bullets that won World Wars I and II. But in the 1980s, the last of the big mines shut down. Now, most of the riches are gone, and Butte is struggling.

All that mining left a big toxic mess – so toxic that for the last 30 years, Butte has become famous again. This time, for being the epicenter of one of America’s biggest and most intractable Superfund sites.

I had the chance to spend last weekend in Butte, Montana for a wedding. While I was there for less than 48 hours, I got quickly sucked into the story of this company town. This limited series podcast is a great overview of the city, the Anaconda Copper Company, and the environmental legacy that has been left behind.

Not Built for This #1: The Bottom of the Bowl, 99% Invisible, Limited Series

Reporter Emmett Fitzgerald was used to hearing people call his home state of Vermont a “climate haven.” But last summer, he got a wake up call in the form of a devastating flood.

All throughout the United States, people are watching the places they love change in unpredictable and scary ways. Places that once felt safe are starting to feel risky. Places that already felt risky are starting to feel downright dangerous. And as the climate continues to change, people are being forced to make impossible decisions about how to live, and where to live, in an increasingly unstable and unfamiliar world.

The first episode of this series is a really good on-the-ground illustration of what small cities look like in the wake of more intense and frequent weather events. I’m looking forward to the rest of the series.

You can reach me at dustin@invanti.co if you want to chat more about the small city segment!