More of Different

Why small cities should consider optimizing for weird in their entrepreneurial ecosystems

PSA: I’m trying something new. At the end of all posts, I will give a short rundown of topics I’m actively researching, questions I have, and people I’d love to connect with about them. Read on to see previews of problem profiles in the works!

A bias I have in my framing of innovation-driven entrepreneurship is a problem-first perspective. I gravitate toward entrepreneurship driven by recognizing unmet needs versus by creating a vision of the future. I don’t think one is necessarily better or more important than the other - we probably need both. Maybe it’s my engineering background, but the problem-first approach is just more intuitive to me.

Problems aren’t enough though. You need to build solutions that offer better tradeoffs to your customers, you need to build a viable business, and you need to be able to constantly find new ways to solve the problem better than your competition. The recognition of a problem is a requirement of success, not a guarantee of it.

I’ve written so far about the problems that exist in small cities and the opportunities those represent for new startups. But to act on these problems, you also need people with the capabilities to understand them, solve them, and build a business based on them. This post is an early exploration of how small cities might steal an idea from economics to do this in a competitive age where almost every city, state, and country is trying to do the same.

Economic Complexity

I listened to an episode of the Odd Lots podcast this week on Economic Complexity with Riccardo Hausmann, an economist at the Growth Lab at Harvard.

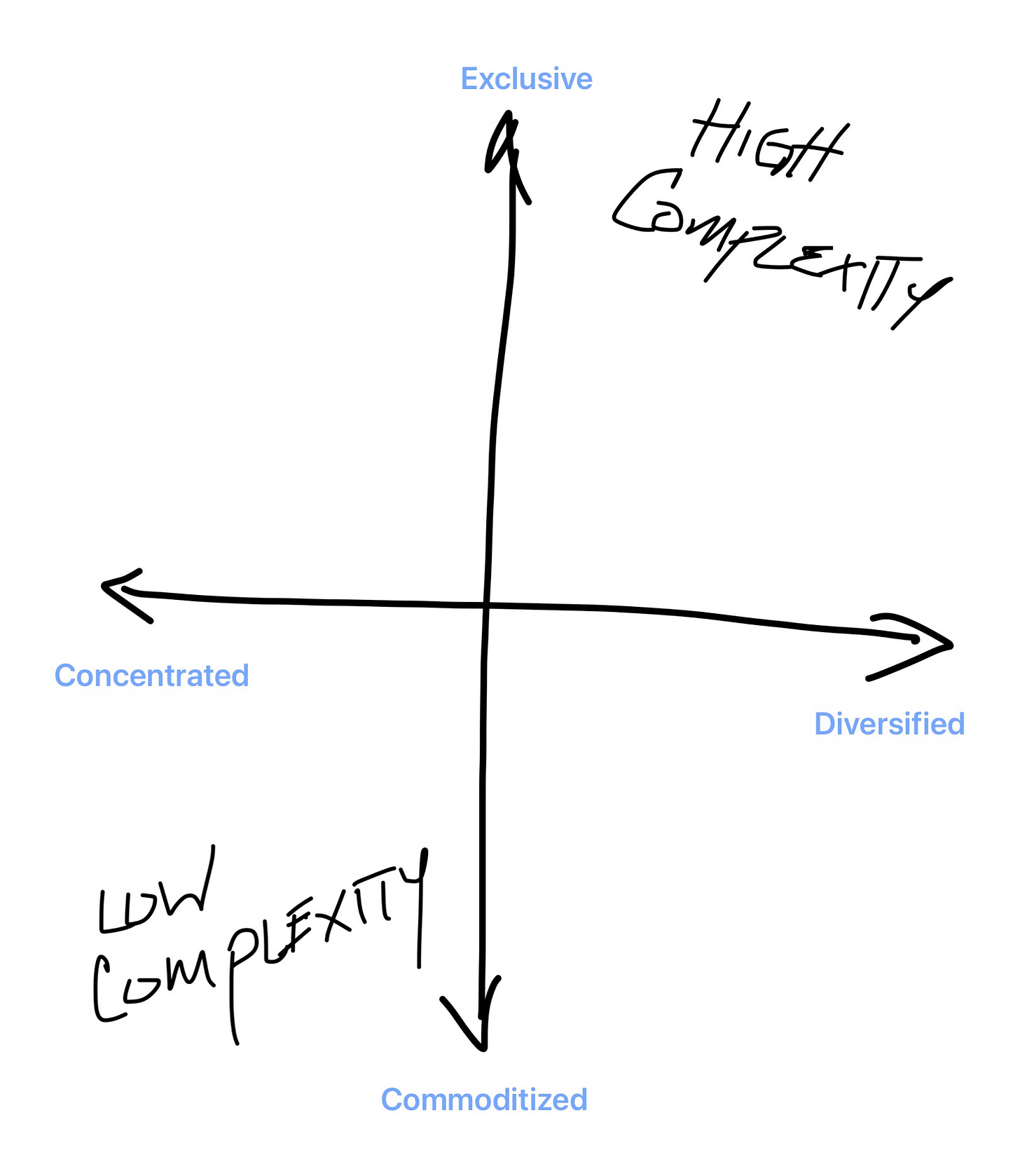

The basic idea is that when it comes to the global economy, the wealth (measured by GDP per capita) of a country is highly correlated with its “economic complexity”. Economic complexity is a measure of (1) how many types of products/services your country produces and (2) how different those products/services are from what other countries produce. A country with high complexity produces many types of products/services, most of which are exclusive to that country. A country with low complexity produces very few types of products/services, most of which are commodities. A simple 2x2 matrix would look something like this:

The model also suggests that complexity is a result of capabilities. The products your country can produce is a result of the capabilities and knowledge of your residents and organizations. So to change complexity, you need to change capabilities.

This makes a lot of sense intuitively. If you are producing a lot of different things, you need a lot of capabilities to do so. If those things are also very different than what others are producing, you need a lot of different capabilities.

Not only have the researchers found that high complexity is correlated with higher wealth, they’ve also found it to be indicative of growth patterns. Countries with below average GDP per capita, but high complexity tend to grow in the future while countries with above average GDP per capita but low complexity tend to shrink. The episode is full of great analogies and examples if you want to get a more thorough understanding. You can also read the working paper here.

The interesting thing about this two-dimensional view is that adding capabilities is not enough. That may increase your score on the diversification axis, but it does nothing for your differentiation axis. What you really want is to add differentiated capabilities. And the holy grail is to produce products that require a combination of capabilities. Combining two or more capabilities can produce exclusivity - and the more differentiated the underlying capabilities, the harder that combination is to reproduce elsewhere.

In short, countries should aim to add more and differentiated capabilities. From the discussion section of the working paper:

This paper has not emphasized the process through which countries accumulate capabilities, but has instead focused on their measurement and consequences. However, the results presented here suggest that changes in a country’s productive structure can be understood as a combination of two processes (i) that by which countries find new products as yet unexplored combinations of capabilities they already have, and (ii) the process by which countries accumulate new capabilities and combine them with other previously available capabilities to develop yet more products.

A possible explanation for the connection between economic complexity and growth is that countries that are below the income expected from their capability endowment have yet to develop all the products that are feasible with their existing capabilities. We can expect such countries to be able to grow more quickly, relative to those countries that can only grow by accumulating new capabilities.

There is a great segment of the podcast (minutes 20:23 - 26:00) where they talk about how a country can create more complexity. Hausmann offers three paths:

Adjacent Possible - the easiest way to create more complexity is to combine capabilities that you already have in new ways. An example would be combining the capabilities from an existing industrial sector that understands building pumps and an existing healthcare sector that understands carrying out complicated surgeries.

People Immigration - the second way is to add new capabilities through immigration, attracting people who have different knowledge than your current population. An example would be a country incentivizing immigration for STEM educated individuals through a streamlined visa process.

Capability Immigration - the third way is to add new capabilities to your existing residents’ repertoire through them learning in another place that has different capabilities. Hausmann has a great story in the podcast about how a company in Bangladesh sent over 150 employees to South Korea to learn the garment industry. Within a few years of returning, over 50 started their own companies, which now form the backbone of their garment industry.

Startups as Products

What does this have to do with small cities and startups? I think we can apply this framework to the startup ecosystems that small cities are trying to build. One of the “products” of economic development is new businesses, and lately, new businesses with high growth potential. Just like any other product, those startups need to compete with the startups coming out of all the other ecosystems for things like capital, talent, and customers.

If we consider startups as the products, then it follows that they are the result of the entrepreneurship ecosystem’s capabilities. And the strength, and future growth potential, of that ecosystem can be measured by its complexity - i.e., the diversity of types of startups in that ecosystem and the exclusivity of those types of startups to that ecosystem. In other words, ecosystems would want to constantly pursue more of different. And that more of different is the result of combinations of both new and existing capabilities.

More of Different

There is an interesting book about the history of Silicon Valley called The Power Law, written by Sebastian Mallaby. It details how Silicon Valley has developed since the early 1950s through the lens of the venture capital model. The driving thesis behind the book is that the development of financial capital structures to match emerging technologies is what created the system we all know today.

The complexity model seems to be another way to explain this. As Arthur Rock in the 50s brought his East Coast knowledge of finance to SV and interacted with the semi-conductor industry, new products (and capabilities!) emerged. This then became a positive feedback loop, as this progress enticed more people to migrate to the Valley, each bringing new capabilities to compound on what was being created.

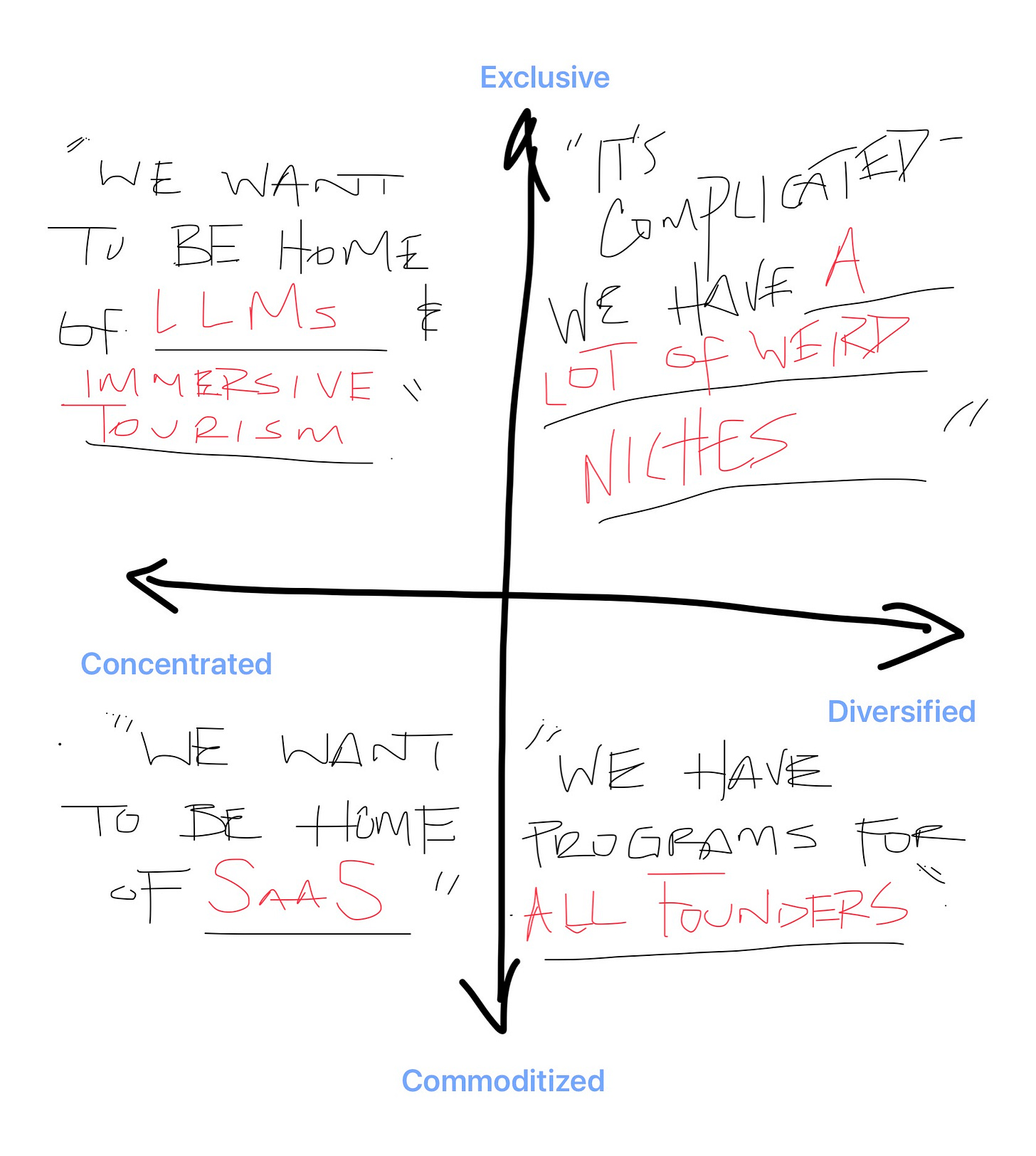

What this tells us though is that every ecosystem is actually emergent. In other words, no one designed Silicon Valley upfront. It evolved from an initial set of conditions in unpredictable ways. This is why copying what has worked elsewhere seldom works - or at a minimum seldom creates any sustainable advantages. Small cities often find themselves wanting the results of more mature startup ecosystems, but have no playbook besides imitation. You'll hear leaders say things like, “We don’t need to be the next Silicon Valley, we just need to be the next version of us.” This sentiment makes sense but oftentimes lacks a strategy to accompany it. This can be really frustrating. I’ve personally struggled to find a clear framework for how smaller cities can find their unique identity.

But if we steal the complexity framework, it turns out they don’t need to define it upfront. They don’t need to proclaim “We want to be the home of [insert new technology/sector here]”. Small cities can instead focus on four inputs:

Reviewing the current and historical capabilities unique to the city

Getting current residents new and differentiated capabilities

Attracting new residents with new and differentiated capabilities

Increasing the chances of weird and new combinations of all these capabilities

It’s pretty obvious when looked at it this way, but it requires something that can be difficult in small cities - a focus on and comfort with being different. It is tempting to create programs, investment groups, co-working spaces, accelerators, etc. that replicate what seems to have worked elsewhere. And there is some value to learning from what has worked and to even stealing some of it. But the real results will come from being weird - from trying things in odd combinations that others won’t and can’t. Instead of focusing on being a “great place to start a company”, they can instead focus on being the only place to start a certain type of company.

In fact, a large part of the economic history of these places is tied to developing weird niches. For example here in Indiana, Fort Wayne is known for specialty insurance. Elkhart is the RV capital of the world. Warsaw is the home of orthopedics. These arose from years of compounding combinations of capabilities. We’d do well to think about the weird combinations we can stack on top of the capabilities in these industries and see what weird things come from it.

We don’t have to predict what the next weird niche will be in these small cities - we just need to focus on being weird. But that’s hard. It requires a focus on process, not outcomes. It’s giving up on a deterministic path and trusting that if you get the inputs right, something good will happen, even if it’s not predictable exactly what that is. It requires an understanding of the economic history of small cities, the future of technology, and a belief that more of different is valuable.

What I’m Working On

These are all threads I’m pulling on for future Problem Profiles. I’m not sure if they will make the cut yet for a full post, but I’m trying to learn as much as I can about them to find out. Any and all resources, connections, or first-hand accounts are welcomed!

Reduction in Health Care Services Offered

After writing the Small City Segment piece, a friend who has spent his career in healthcare wrote to me that it made him think of an interesting dynamic in healthcare that’s happening. As more PE firms and large hospital systems buy up small practices, there are a lot of cuts to services happening because of low margins and low volumes. This is leaving some services deserts, forcing people in smaller markets to have to travel to larger ones to receive care. If you know anything about this or anyone who might, please let me know!

Public Bus Transportation Incentives

Another topic that came up in a conversation about the Small City Segment was the government incentives around purchasing buses and how it may be leading to oversized buses being used when a larger fleet of smaller buses might make more sense. If you know anything about this or anyone who might, please let me know!

Costs of Sales

A common reason given for not selling into smaller markets is the costs of selling into them. This can limit what technologies make their way into these markets, especially for smaller firms. One example someone mentioned to me would be the software vendors available to small, independent physician practices - only the largest ones can afford the costs of sales, but that also means that small firms are a marginal customer and therefore not served particularly well. If you have stories or people that struggle with either side of this dynamic, I’d love to hear from them too!

If you…

are interested in building for the small city segment…

are already building for the small city segment…

know someone who might be/should be building for the small city segment…

want to contribute expertise to problem profiles…

or want to help us expand our networks of trust in small cities…

please reach out at dustin@invanti.co.

Works cited in this essay:

How Economic Complexity Explains Which Countries Become Rich, Odd Lots Podcast

The Building Blocks of Economic Complexity, César A. Hidalgo and Ricardo Hausmann

The Power Law, Sebastian Mallaby

Other works that influenced this essay:

Differentiation, Not Boring