Stick to Value

What is solving that problem worth?

This is the third in a series of in-depth essays that describe our process for creating new startup ideas at INVANTI and the thinking behind it. You can read the first one on finding contradictions here (+ listen to us talk through an example here) and the second on unlocking better tradeoffs here. Subscribe to this Substack to get notified about new essays and podcasts in this series.

Update: In the month of April ‘23, we are running a 4-week Problem Sprint, to help founders define and validate the problem they are working on, based on a the writing we’ve done here in the past two months. It’s open to anyone, free, virtual, and (mostly) asynchronous. You can sign up here.

We’ve covered two big topics so far: (1) finding things that don’t make sense and (2) finding the barriers preventing those things from working better. Those are frameworks that can be extended to a lot of areas outside of startups (we’ve used them with local government and other public-private institutions as well). But one of the constraints of a startup is that it has to solve these issues in a financially self-sustaining way.

Not only that, but if you’re going to take on venture funding, you need to solve these issues in a way that produces outsized, outlier financial results. It’s not enough to be sustainable, you need to produce scale and financial returns that are better than almost any other available.

Most people think of financially sustainable as a simple equation - earn more money than you spend. How much you will spend is usually straightforward to estimate. But how can you estimate how much you will earn if we aren’t even in business yet? This implies a price. But how do we decide on a price? We could just choose one and see if people pay it, but that would be a bit of a shot in the dark. The alternative is to introduce a third variable to this equation - customer value.

When I say “value” here I mean literal, financial value. Not value in the sense of “value proposition” or “yea, I find that valuable”, but value in the sense of “it’s worth $XX”. This is also different than price. Price is what your customer pays in exchange for the value.

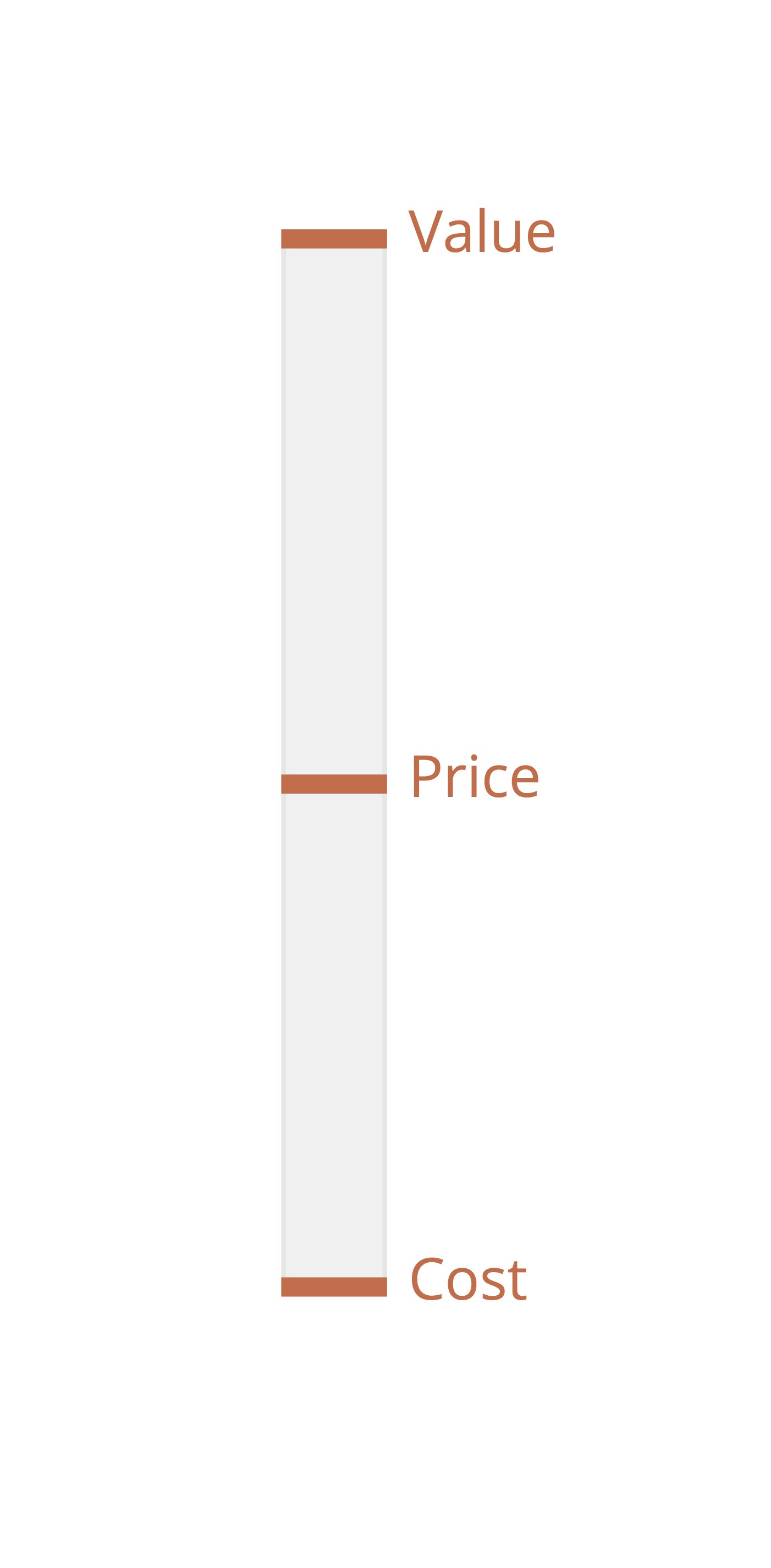

Value, Price, Cost

One of the oddest but good books I’ve come across in business and investing is The Rebel Allocator by Jacob Taylor of Farnam Street Investments. The book is a fictional account of a relationship between a seasoned businessman (loosely based on Warren Buffet and Charlie Munger) and a young guy who is initially skeptical of the business world. It’s fictional format is different for a business and investing book, but it also forces a certain level of simplicity and clarity in explaining the most fundamental business ideas.

One of the more powerful and simple frameworks the older man shares with the younger is what he terms, “The Iron Law of Economic Survival.”

“In order for a business to survive, the value delivered to the customer, V, has to be greater than the price the customer is charged, P, which has to be greater than the cost of that good or service, C. V is greater than P is greater than C.

…They can be in a different order for brief periods of time, but anything other than C then P then V is not sustainable. Either the customer will stop buying, your business will go bankrupt, or both.”

This same concept is talked about in a paper from 1996 by Adam Bradenburger and Howard Sturart of Harvard Business School called, Value-Based Business Strategy (worth the read, it’s fairly short and straightforward - I originally found the paper when Michael Mauboussin mentioned it on Invest Like the Best.) They call it the “value stick” - the idea is very similar, although a bit more advanced and academic. I’ll use a combination of their frameworks for the discussion and illustrations below.

The equation is pretty intuitive - even most kids would catch on fairly quickly. Customers are happy when Value > Price. You’re happy when Price > Cost. Your job is to just keep everyone happy! But it’s often harder than it looks to actually keep these things in balance. What happens if this “Iron Law” is broken? There are three scenarios:

Customers Stop Buying

If Value is less than Price (C < V < P or V < C < P), then the “customer feels cheated” or like they aren’t “getting their money’s worth”. Even if you’re making money (i.e., C < P), they will eventually stop buying.

You’re Losing Money

If Price is less than Cost (P < V < C or P < C < V), then the customer is happy, but “you’re subsidizing the happiness of your customers at your own expense” (or at your VC’s expense!) Eventually you’ll go out of business.

Both!

If Value is less than Price is less than Costs (V < P < C), then customers feel cheated and you’re losing money doing it - the literal opposite of our goal.

However, if we have these in the right order, then we can define a few other things:

Brand Value or Customer Surplus (V - P): The excess benefit the customer gets after paying the price. Another way to look at this is V/P, which is like a measure of “ROI” for the customer. For example, if I pay Costco $60/year for a membership, but it saves me $600 by shopping there, I have a 10x ROI as a customer.

Profit (P - C): This is your profit as a company. For Costco, this is the difference between what it costs them to get me all those great deals and the $60 they charge me per year. Note: we are using profit and cost pretty loosely here. If we were going to do actual calculations, we’d have to think about over what time period? What is a unit? etc.

(If you want to read the genius of Costco’s business model and see how they think about value, price, and cost, check out this deck.)

Especially in B2B (business-to-business) companies, you can see that a supply chain is just a series of staggered and interconnected “value sticks”. One company’s price is another company’s cost. Understanding the value to your customer is akin to understanding the price they charge their customers. None of this is groundbreaking or new, but the simplicity of this framework can force a lot of tough questions as you design a business.

How does this relate to unlocking better tradeoffs for the customer?

The lesson here is that it’s not enough to know price and cost - you need to understand value to your customer. That allows you to both set pricing and determine what costs you can afford, while still generating a profit. To understand customer Value, you need to understand your customer’s “value stick”. What is it worth to them to have this better solution? What value does it unlock? We can then evaluate the strength of the proposition that you’re making to your customer, as well as the strength of the business that would provide it.

How do you increase value?

Visually, you can think about increasing value as lengthening the stick. There are three ways to do so:

Find a way to reduce Cost

Find a way to increase Value

Both!

If you find a way to do one of these, you can then decide how you want to distribute those gains - keep it for yourself (increased profits), pass it to your customer (increased customer surplus), or some combination of the two. All options will allow you to create a stronger business than your competitors. Notice I didn’t mention “Find a way to raise Prices”. While this is a good idea for many businesses (usually because they don’t quite understand the value they are creating, and therefore are underpricing!), it doesn’t create any new value. Put another way, the stick is the same length, you’re just shifting the distribution of value between you and your customer.

Your Customer’s “Value Logic”

In the same way that we need to learn how customers think about the tradeoffs of different solutions, we also need to understand the way they think about the financial value those solutions create. Internally, we call this the process of defining their “value logic” (or “economic value logic”). The idea here is to figure out how they think about it first, then fill in the numbers second.

We often explain this to founders with this scenario: Imagine you’re sitting with your customer. You explain the problem you solve and they say, “That’s it! Tell me more!” You slide them over a pamphlet that details how your solution works and the price. What we are trying to figure out is, regardless of what that magical solution is and what number is on the page, what goes through their head next? How do they decide if that price is “worth it”? What’s the criteria they are using for their own C < P < V equation?

To explore this, we need three things:

What are the metrics of success of the solution, i.e., how do we know the problem is solved?

Who cares about one or more of those metric improving

The logic those stakeholders would use to define the financial value of that metric improving

Step #2 may seem a bit odd at first glance. We will be writing a more in-depth exploration of this in the future, but it can sometimes be the case that your user doesn’t necessarily have to be your customer. In this case, we want the option to explore who else benefits from the problem being solved, and what value is created for them by doing so. This can open up 3rd party business models which can be really effective when your user doesn’t have the ability to pay. More on this in a later essay.

For now, let’s take the simplest case where the user is the same as the customer (i.e., the payer). Here are a few different examples of different types of “value logic”:

The “If-Then” Logic: This logic is the type you most commonly see in B2B companies and involves seeing value directly as cost savings or new revenue. It usually sounds like an if-then statement, e.g., “If you were able to reduce the time I spent on logging potential customer calls by 50%, I could double the volume of reach outs I do and potentially double my monthly sales from $250k to $500k. At 20% commission, that’s an increase of $50k to my annual bonus!”

The “Comparables” Logic: This logic is often common when hard numbers or an if-then statement are harder to come by or quantify. In this case, they may think through value as some comparison to similar things. For example, at one time we were exploring a subscription product for some of our frameworks and I asked a potential customer how they would think about the value. She said, “Well, I’d consider using your process as an investment in myself - much in the same way that I spend money on other things that I do just for me. So for example, I spend $50/month on manicures/pedicures that I consider a “just for me” thing, so I’d put it in a bucket like that.” Now this looks a bit more like price rather than value, but there is at least an anchor here. I knew if I came back with a $500/month product, I’d probably be an order of magnitude off in the value equation. I love this example because it was so unexpected, but rational nonetheless.

The “Opportunity Cost” Logic: This one is the hardest to pin down or predict, but when the first two logic types are absent, sometimes people anchor to what else they would do with the money. This feels the most common in consumer products that have no clear financial outcome. An example logic here might sound like, “I just cannot imagine spending more than $5,000 on a mattress - you can find a used car for that kind of money!” Again, this can sound more like price than value, but in the absence of a clear if-then logic, this can help build some guardrails and let you at least understand orders of magnitude.

What makes for strong value logic?

In this case, this is pretty straightforward - it’s strong if (1) we can define it and (2) we have reason to believe it would leave room for profit. We don’t have a solution or business model yet, but you can use some intuition here and some back-of-the-napkin math to get a read on if this leads to a viable business or not.

The ideal type is the if-then type, but this isn’t always possible and its absence doesn’t necessarily mean you have weak value logic either.

What makes for weak value logic?

Weak value logic is either (1) one that we cannot define or (2) one where it seems highly unlikely that there is room for profit. The first is far more dangerous because you can always convince yourself that we can figure it out later. Press hard if you find yourself in this position to figure out why it is so hard to define.

Discovering Value Logic

Unlike past essays, this process is really more about discovering than creating. I’ll also warn you that this usually is a barbell of difficulty - sometimes it’s almost too obvious, and sometimes it seems impossible. Even if it seems illusive, going through the process is really valuable because it makes you ask deep questions about what value you’re unlocking and for whom. It can also allow you to be creative with business models. Unlocking 3rd party payers who are aligned with the same success metrics can make for innovative business models, especially for those who have traditionally been locked out of certain products and services because of cost.

(If you’re interested in the workspaces we use in the Founder Studio to do the process outlined below, click here and we can send you a copy you can use.)

Review the need you are meeting for your customer

Remind yourself of the customer, the need you are solving for them, and why they ultimately care about that need being met.

List success metrics

Create a list of what your customer would/could measure to know the need is being met.

List who else benefits

With the metrics in hand, for each think about what other stakeholders benefit if that metric improves. Important note: for stakeholders you haven’t talked to yet, validate that this is actually true!

Choose the most compelling Stakeholder - Metric pairs

You may have a few or many pairs between your metrics and those that benefit. Choose the 1-3 that are most compelling or interesting to you.

For each pair:

Make explicit how the stakeholder benefit. How exactly is the stakeholder better off?

Note if they already pay to improve the metric, and if so, from what budget

Choose one pair and draft a hypothesis of the value logic

Based on your discussions, create a draft logic. Don’t worry about the numbers yet - just worry about the structure of how they think about value.

Show this to stakeholders and iterate

You’re probably wrong and that’s ok - show it to people, take their feedback, and iterate it!

Plug in the numbers

Now that you have the structure right, you can start to use back-of-the-napkin numbers to get to an actual amount of money.

Summarize into a Value Logic Statement

Once you’ve done this, summarize into the following Mad Lib:

[$X] of value is unlocked when [metric] improves for [stakeholder]

Repeat steps 6-9 for each pair

Evaluate the Value Logic Statements

This is a bit subjective, but review the value logic statements you have to see which are strongest. Are any if-then types? What is the relative importance of the value to each stakeholder? Are some more important than others?

Choose one

As always, use all the context you have to choose the one you think would be interesting to build a business model around.

Patterns of strong value logic:

It is clear to your customer how they would evaluate the financial value

This sounds a bit circular, but you’d be surprised how often people say they love the idea of a product/service, but cannot tell you how they would value it! The clearer the logic is for them, the easier it will be to get them to be (and stay) customers.

They already pay for the metric to be improved

This means we can already get a sense for how they value it, what they pay, and potentially what it costs the current solution provider (V-P-C!)

There is a clear economic outcome

This isn’t necessary, but it makes things easier, especially in the B2B world.

Patterns of weak value logic:

The customer thinks the idea is “cool” or “interesting” but cannot tell you how they would value it

Their excitement about the solution is not matched by the way they would value it

What’s next?

The next essay will talk about how we translate this customer-centric definition of value into questions about the overall business opportunity. How big of an opportunity is it? Is this problem growing in size and/or intensity? What trends are in your favor? Which are headwinds? This will help us answer the “why now” question.

If you’re interested in the workspaces we use to define value logic in the Founder Studio, click here and we can send you a copy that you can use. Better yet, if you’re interested in working with us to do it together, apply for the Founder Studio here

Written in Lex

Works cited in this essay:

The Rebel Allocator, Jacob Taylor

Value-Based Business Strategy, Adam Bradenburger & Howard Sturart

Sharpening Investor & Executive Toolkits with Michael Mauboussin, Invest like the Best

Other works that influenced this essay:

Monetizing Innovation: How Smart Companies Design Product Around Price, Madhavan Ramanujam & Georg Tacke