Unlocking better tradeoffs

Startup opportunities are about finding what’s hard about offering something better

This is the second in a series of in-depth essays that describe our process for creating new startup ideas at INVANTI and the thinking behind it. You can read the first one on finding contradictions here and listen to us talk through an example here. Subscribe to this Substack to get notified about new essays and podcasts in this series.

Update: In the month of April ‘23, we are running a 4-week Problem Sprint, to help founders define and validate the problem they are working on, based on a the writing we’ve done here in the past two months. It’s open to anyone, free, virtual, and (mostly) asynchronous. You can sign up here.

Points of View & Strategy

We ended the last essay with a process to find contradictions as a first step to developing a new startup idea. What do we do next?

You can think of the contradiction as a premise to a movie. We’ve set the scene - hopefully with some drama - and now we want to explore the story in more depth. Who are the characters? What do they want? How are they interacting? How does the premise affect them? We want to take these points of view so we can choose where in this story we might want enter as a new character. Where do we see an opportunity to change the plot in a surprising, but logical way?

One way to think about taking a point of view is through the lens of strategy. My favorite definition of strategy is the tradeoffs you make in pursuing a goal. With this definition, you realize that analyzing strategy actually requires a lot of empathy. You must understand how someone else views tradeoffs and why they would chose one set over another.

Framing strategy as tradeoffs is especially popular in the business and corporate world. Whether using the famous 5 Forces or 7 Powers frameworks or others, there are a lot of ways to analyze companies, the tradeoffs they are making, and how those choices influence their positions in the market. Increasingly, these frameworks are showing up in startups as well. Investors and founders are thinking about them earlier and earlier in a company’s lifetime. People like Ben and David at Acquired, Nathan Baschez at Every, and Packy McCormick at Not Boring have built them into the DNA of their analyses of early-stage companies.

Usually the main character of these analyses is a company. But we don’t have a company yet - we have a contradiction. How can we talk about tradeoffs this early? We can use this framework if we look at tradeoffs from another point of view - that of your potential customers.

What’s their strategy?

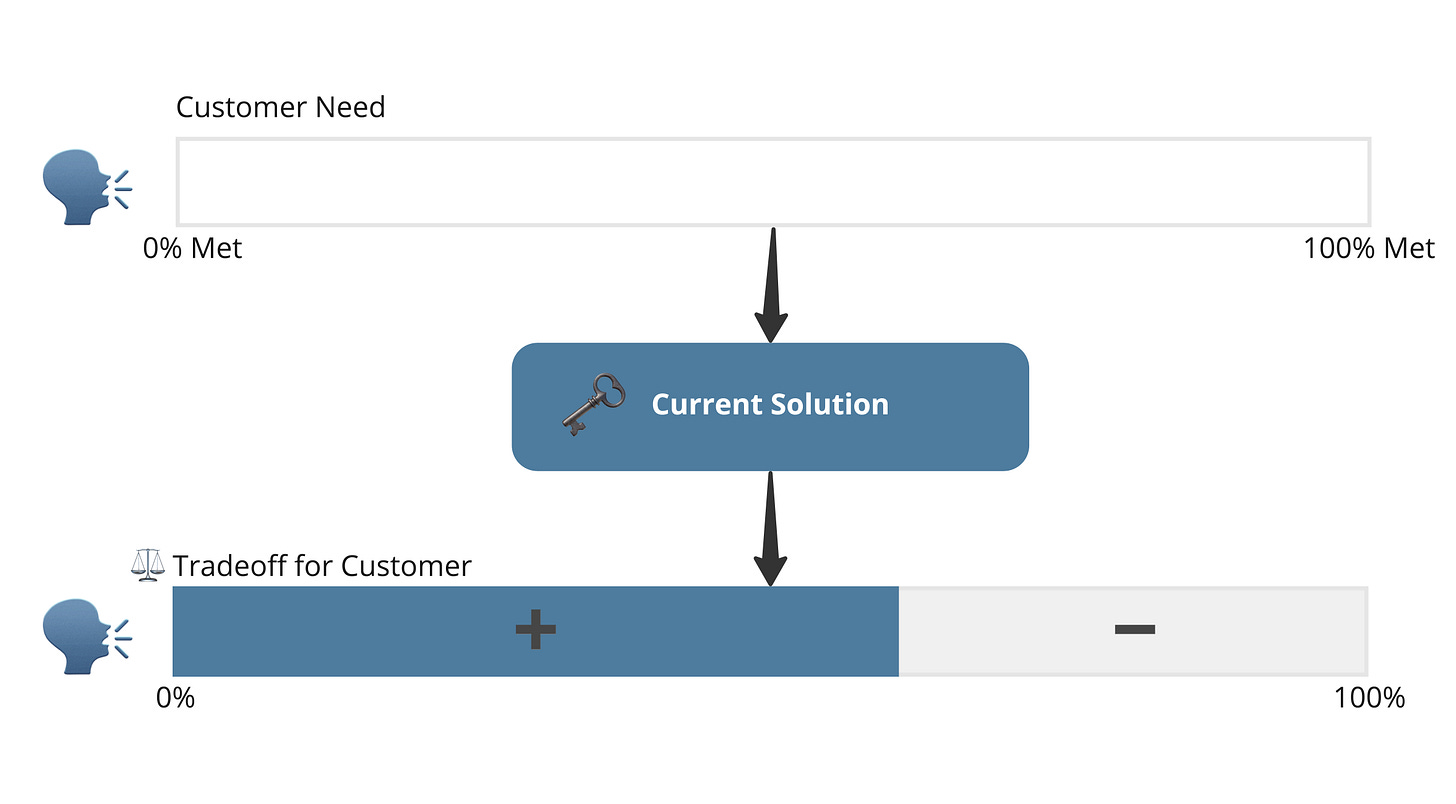

Every time a customer makes a choice about a product or service, they are choosing a strategy to solve their problem. No solution is perfect, so customers are choosing a set of tradeoffs when they make a purchasing decision. The tradeoffs they choose are dependent on a lot of factors - the need they are trying to meet, the context of other solutions available, and the preferences they have. That means that we have to think about customers, needs, and solutions as sets. Change the customer, or even slight things about them, and the tradeoff one solution offers might be viewed differently. Same with choosing a different solution for the same customer. The narrower you define the customer and the need they are trying to meet, the easier it is to understand the tradeoffs at hand and how they are evaluated.

This is why one contradiction can actually produce a lot of different startup ideas - it all depends on whose point of view you look at it from. Our goal here is to ultimately chose a stakeholder to serve - one we think there is an opportunity to serve better. But what is an “opportunity”, exactly? We think about it like this:

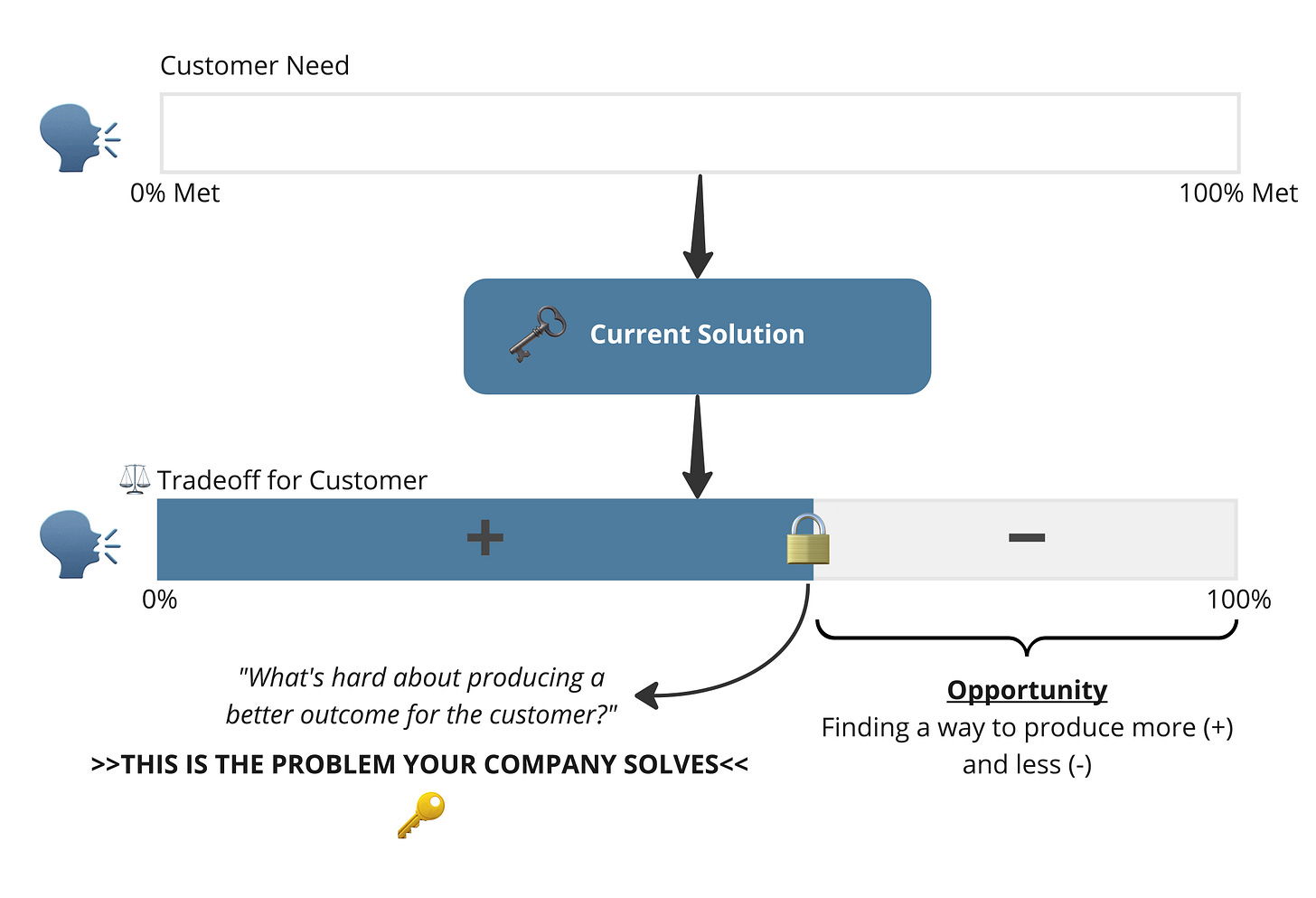

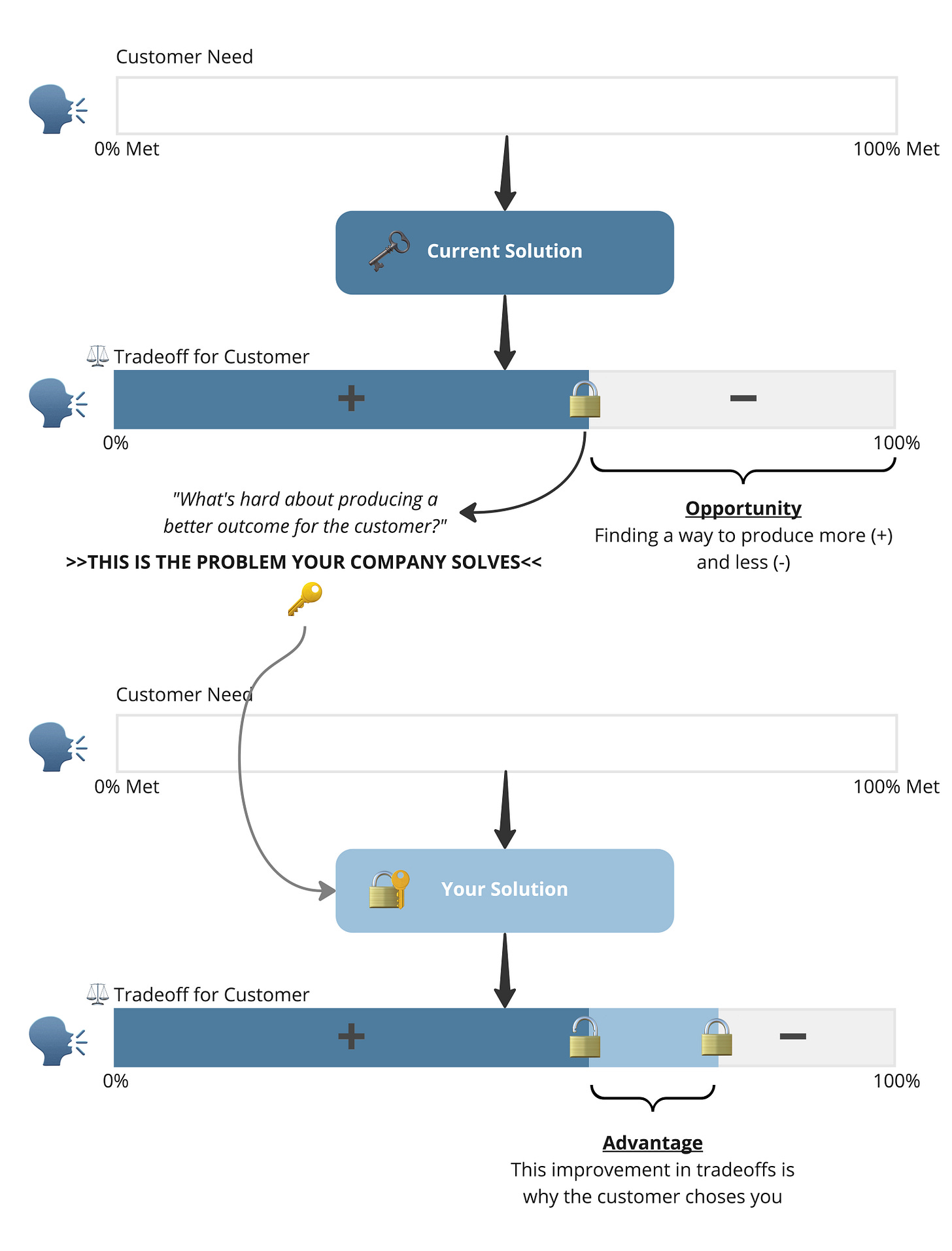

If a customer’s strategy = the tradeoffs they choose, then opportunity = finding a mechanism to produce a better tradeoff for your customer, but that others haven’t made work or are choosing not to use.

If we want to identify a better tradeoff for a customer, we need to understand who the potential customers are, the problems they are trying to solve, and their current options for doing so.

The Problem You Solve

The internet is full of content about needs finding. Personas, jobs-to-be-done, needs statements, pains and gains, value proposition design - there are a lot of useful frameworks out there. This is really important work that has to be done. I won’t spend a lot of time on it here because there are so many other resources available. But what I do want to talk about is a conflation that often happens in this part of the process that can be the difference between identifying a compelling opportunity and not.

The idea of first defining the problem you solve as a startup, before deciding on a solution, has been widely shared and adopted by now. However, it’s really hard to find a good definition for “problem”. And because of this, many founders end up conflating the customer need with the problem their startup is solving. These are related, but actually different things. There is a difference between the problem your customer needs to solve and the problem you solve.

The customer need is the outcome they seeking:

“I need a way to understand who on my team would be best to upskill into new positions we have open.”

“I need a quick and affordable way to understand how this question in the immigration process applies to my specific situation.”

"I need a way to buy a house within my budget and start building equity.”

The problem your startup solves is whatever is getting in the way of that outcome happening. You’re trying to solve the shortcomings of the solutions they are using today. In doing so, you find a way to produce a better tradeoff for your customer.

» Problem you solve ≠ the customer need

» Problem you solve = what is getting in the way of the current solutions better fulfilling the customer need

What you’ll notice then is that it’s not enough to understand what the customer is trying to achieve when you’re doing customer discovery. We want to know those goals in the context of what they are doing today. Competitive analysis isn’t just something you look at once you’ve settled on a solution - it is part of determining what your solution should be in the first place.

You’ll also see that I keep saying “Current Solutions”, not “companies”, or even “competitors”. Often times, especially in underserved markets, there are no companies that exist to meet a customer's needs, so the solutions they are evaluating tradeoffs for are informal or DIY work-arounds. This doesn’t mean you don’t have competition - it’s just not a company.

Different with a Difference

What is counter intuitive here is that especially at this early stage, your competitive advantage is not about the difference between what you and your competitors do. Customers don’t care about what’s different about what you do - they care about what’s different for them because of what’s different about what you do. Too many founders are focused on what they do differently, without asking if it matters. If you’ve done problem definition well, you will naturally decide to solve something that the alternatives can’t solve, won’t solve, or have decided to ignore.

» Competitive Advantage ≠ what’s different about what you do

» Competitive Advantage = what’s different for the customer because of what’s different about what you do

Another common mistake is founders choosing tradeoffs that will be better for the business (e.g., “subscription business models are better”; “pure software has better margins and can scale”; etc.). The real game is about finding tradeoffs that are better for the customer - then it’s your job to solve the puzzle of making that tradeoff a reality.

(Investors are really the ones choosing which business tradeoffs are more interesting. They in some ways are a third party observer, so they can make these kinds of choices. One problem we see is founders tailoring building a business towards what they think VCs want from a business strategy perspective, not what customers want. Which is ironic, because great VCs want to invest in founders that know what customers want.)

To recap:

Once we have a contradiction, it’s time to find if/where there is an opportunity to act in a way that changes the plot and resolves the tension. Identifying an opportunity is not just about knowing what the customer wants; it’s about defining what is currently hard about giving the customer what they want.

Often the customer need is not actually all that complicated. People like things better, stronger, cheaper, faster, etc. How to give them that is the question - and that’s where knowing what others are doing/have done is key.

A common piece of startup advice is to ignore the competition early-on. I think it’s a bit more nuanced. Once you identify the opportunity in the context of the current solutions, then don’t worry about competition. But before you know this, all you care about is competition. We want to find what’s hard about making things better for the customer. That’s the problem to solve.

What makes for a strong opportunity?

High ratio of negatives (-) to positives (+) in the current tradeoff for the customer

e.g., to continue our Hurry Home example from the last post, people who chose to continue leasing were paying 2x in rent what they would pay to buy and were missing out on building equity

Solving the barrier would produce a better tradeoff for the customer

e.g., the barrier to homes under $80k being financed with a mortgage is that banks have a hard time doing this profitably because their fees are capped at 5% of loan value (i.e., cheaper the home, smaller the fee). This makes it hard to justify a $50k house, when you can do the same work for a $300k house. If you could find a way to make financing low-dollar homes profitable, customers would (1) save money monthly, (2) build equity in an asset, and (3) have more housing stability

The barrier to producing a better tradeoff is (1) widely unknown, (2) widely misunderstood, or (3) requires a specific and uncommon set of skills

e.g., the widely held narrative about the affordable housing crisis is that homes are too expensive to finance, and in this particular case, they are actually too cheap to finance

In the form of an opportunity statement, we can summarize this as (see below for more on this Mad Lib):

People making under $35k/year (e.g., nurses, teachers, service workers) who currently rent, have a good rent payment history, and have credit scores above 650 need a way to finance a home purchase under $80k, but banks avoid making these loans because their fee structure makes them unprofitable to underwrite.

What makes for a weak opportunity?

Diminishing returns on improving the tradeoff offered to the customer, e.g., current solutions offer high positives (+), low negatives (-) already

e.g., I’d put standalone “round-up savings apps” in this category. Yes you can help people save more, but based on the magnitude, it may be more of a feature for current companies than a way to build a new company

The barrier to producing a better tradeoff is structural and potentially better solved with policy or other non-entrepreneurial approaches

e.g., there are a lot of opportunities in healthcare in the US and there are also a lot of places where the system and policies as a whole make it hard to address them

The barrier to producing a better tradeoff requires a specific and uncommon set of skills, but you/your team don’t have them

This is probably one of the most common that we see. A lot of people have an instinct that certain technologies or business models could solve a problem, but don’t actually have the skills or the team to use them (very common with AI and blockchain right now)

Finding Opportunities

With the contradiction in hand, we can start to explore where opportunities might be. We can examine different stakeholders involved, different needs they have, and different current solutions the are using. This can create a lot of different combinations and angles for a startup - all predicated on the same contradiction. This is what makes this process so much fun. There are a lot of ways to attack these problems and you can start to optimize for the opportunities that best fit you and your founding team’s skills and interests. Below is an of outline the step-by-step process we use to do this.

(If you’re interested in the workspaces we use in the Founder Studio to do the process outlined below, click here and we can send you a copy you can use.)

Define the Stakeholders:

Who are the stakeholders involved in this contradiction? Be exhaustive - we can always trim the list later.

Talk to the Stakeholders

For as many of the stakeholders as possible, talk to a few that fit the persona. These conversations should be very similar to the ones you had during the contradiction stage, just narrowed a bit now to only chat about the premise of the contradiction you’ve found. Again, stories are where the magic is.

Define their Needs

What are their needs as it relates to this contradiction? The more specific about both the stakeholder description and the need you can get the better. You can use this simple Mad Lib to help you get started:

[type of person] needs a way to [need]

Chose one Stakeholder <> Need Set

Chose the stakeholder you want to pursue next. This can be based on who you have access to, who you are most excited/intrigued by, who you think is suffering the most from this issue, or any other criteria. Again, we can always circle back to try another one if we hit a dead end.

List the current solutions you know

For the need and stakeholder you’ve chosen, list all the current solutions available to them. This list should come from what you’ve already heard in your conversations with stakeholders or what you’ve found in your research. It’s important to not limit the current solutions to just other startups or companies. Think about anything they are doing to solve this problem now: non-profit solutions, policy solutions, DIY/informal solutions, and - sometimes the most important one - the “do nothing about it” solution.

Talk to the stakeholder again

Once you have an initial list, we want to talk to the stakeholder we’ve chosen again. This time we are after two pieces of information. First we want to know if there are any current solutions we are missing. Secondly, we want to know for the current solutions we have, how the stakeholder sees the tradeoffs. What works about them? What doesn’t work about them? Note: you can ask these questions even if the person has never used the solution - just ask if it was presented to them, what would they think about it?

Define the tradeoffs

For each current solution, create two lists. The first list is what works about the solution. The second list is what doesn’t work about the solution. Both lists should be created from the perspective of the user, not you.

Define the barriers to change

For each current solution and accompanying list of tradeoffs, answer “What is preventing the solution provider from offering a better tradeoff?” These aren’t necessarily going to come directly from your conversations - they might be a synthesis of everything you’ve learned, or even a hypothesis at this point.

Summarize into an Opportunity Statement

Choosing one barrier to change, or a few that are related, we can now synthesize all the pieces together into a simple Opportunity Statement:

[type of person] needs a way to [need], but [insight about current solutions].

You’ll notice that this closely resembles the contradiction, but now with a point of view. It should have some of the same characteristics - surprising, but true; resonates with the “type of person”, but uninteresting or unbelievable to others. Again, this may take some synthesis and workshopping to get right. It’s ok to still be a bit awkward to say and explain at this point.

Repeat Steps 4/5-9 until exhausted

You can continue to repeat this process at whatever step you chose. You can choose a different stakeholder, a different need, uncover new solutions, choose a different barrier to change, etc. Building a collection of Opportunity Statements is great because if certain ones don’t play out, you can return to others.

Evaluate the Opportunity Statements

Once you have a bank of Opportunity Statements, start evaluating them. Do they pass the following tests:

High ratio of negatives (-) to positives (+) in the current tradeoff for the customer

Solving the barrier would produce a better tradeoff for the customer

The barrier to producing a better tradeoff is (1) widely unknown, (2) widely misunderstood, or (3) requires a specific and uncommon set of skills.

[bonus test] Does it have some of the characteristics of a strong contradiction?

Chose one

Once you have a set that passes the tests for a strong Opportunity Statement, it’s time to pick one. This is subjective and all about what resonates with you. Which are you most interested in? Which feels like it drives further curiosity? Which creates an emotional reaction of frustration or anger? There is no right answer here, but you should be able to explain why the Opportunity Statement you’ve chosen is a fit for you.

When people ask what problem you’re solving with your startup, this opportunity statement is it - this is the actual problem you solve. You can use the contradiction to set the scene, and the opportunity statement to explain the how you’ve chosen to resolve it.

Patterns of strong opportunities:

Pursuing scale has made a current solution provider converge to an “average” tradeoff scheme that doesn’t really work because no one is really the “average”; i.e., everyone uses it, but they all kind of hate it (Quickbooks?…)

Current solution providers are doing what’s best for them; not the customer

Especially when a short-term incentive (especially at a small scale) is attractive enough for the current solution provider to offer a less-than-ideal tradeoff to the customer; e.g., independent sellers using legal technicalities to get out of lease-to-own contracts repeatedly so they can lease a home to another tenant

An overlooked and/or emerging customer segment…

is currently using a solution designed for a segment with a different tradeoff preference; e.g., immigrant parents using their child’s Venmo account to accept payment or pay bills because they don’t have or trust a bank account

currently has access to a small set of current solutions, most of which are informal or DIY;

Patterns of weak opportunities:

The most common pattern we’ve seen for weak opportunity statements is when founders aren’t able to actually articulate “what is hard about making it better”. Sometimes it’s because they haven’t gone deep enough on current solutions, sometimes it’s because it just isn’t clear.

What’s next?

The next essay will show how we go more in-depth about the actually economic value of this new tradeoff that you are trying to unlock. Is it enough to be compelling to the customer? Does it create enough value to build a business? This will allow us to understand if a startup is actually a good solution for this opportunity.

If you’re interested in the workspaces we use to find opportunities in the Founder Studio, click here and we can send you a copy that you can use. Better yet, if you’re interested in working with us to do it together, apply for the Founder Studio here.

Written in Lex

Works cited in this essay:

5 Forces, Michael Porter

7 Powers, Hamilton Helmer

7 Powers with Hamilton Helmer, Acquired Podcast

Finding Power: How to do Market Analysis, Nathan Baschez

Shopify and the Hard Thing about Easy Things, Packy McCormick

I saved £150 in a year without doing ANYTHING – and here’s how you can too

Other works that influenced this essay:

Differentiation, Packy McCormick

“The value chain” is the DNA of business, Nathan Baschez

It’s Time to Re-Build, Sydney Thomas

Sharpening Investor and Executive Toolkits w/ Michael Mauboussin, Invest Like The Best

“Strategy is about tradeoffs. By choosing one thing, you reject something else. To understand a company's strategy, it is not enough to know what it tries to achieve; it is equally important to understand what it doesn’t do.”