Problem Profile: Mortgage Economics at the Edge

The economics of mortgages make housing under $150k too affordable to finance

This post is part of our Problem Profile series. We showcase issues that show up uniquely in small cities, but present big opportunities to build businesses. Subscribe to see future Problem Profiles, as well as other content about the Small City Segment.

Imagine you’re a mid-20s go-getter who just took a new job in the mortgage department of your regional bank. You’ve always had a knack for sales and talking to customers and are excited to help people achieve that goal everyone talks about - homeownership.

When you signed your offer letter to be a Mortgage Loan Officer, you were excited by the compensation structure. You have a guaranteed base salary of $45k, with a commission of 0.5% of the loan value of each mortgage your originate. You really love the idea of uncapped upside, based on the amount of time and work you want to put in. You’ve been listening to The Loan Officer Podcast, learning how mortgage loan officers get paid and best practices in your first year. Your goal is to make at least $75k in this first year of work, meaning you’ll need to close $6M worth of mortgages to make the extra $30k you need to get there. You sit down to lay out your goals and start to think about how to achieve to $6M in sales.

After doing the math, you feel like aiming for the $200k-$300k range is where the sweet spot is. Any lower and you’re just going to have to chase too many leads and close too many loans. You feel like you’ll get to those $500k homes at some point, but it’ll take some time to build the skills and a network of customers to get there.

Percentage Incentive

The hypothetical above highlights a key component of how the housing market operates - nearly every form of revenue is a function of home prices and loan values and nearly every cost is not. Whether you’re a realtor or a mortgage loan officer, you live and die on commissions and commissions are based on home prices. From the perspective of the realty and mortgage companies, this makes a lot of sense. But this simple fact along with others, combined with the size and complexity of the mortgage industry, leads to a system that doesn’t always behave as intended.

One such oddity is a phenomenon that shows up in small cities. Turns out, when housing gets too affordable, the economic incentives of the mortgage market break down.

The Market

For the three years prior to the pandemic, the median home sales price in the US hovered between $300k-$330k. That number has since exploded to almost $500k late last year, but is now trending back down.

Depending on assumptions1 you make for interest rate, mortgage length, taxes and insurance, and downpayment, you’re probably looking at a household income of $90k-$100k to be able to afford the median house value in 2019.

In places like South Bend, IN, Tuscaloosa, AL, or Topeka, KS, the median home values are lower. Below are graphs of the ratio of median listing prices in these metros to the national median. Over the past six years, all three have usually fallen between 50-80% of the national numbers.

In cities like this a median home price might have looked more like $200k in 2019. Based on the same assumptions made above, a household would need something like $65k-$70k in household income to make that home affordable. And as the median implies, there are plenty of homes that fall below the $200k price tag. In other words on a purely affordability basis, homeownership is attainable in these markets for the average household.

(It is important to say that not all small cities on our list have the same housing market dynamics. There are certainly some where housing prices represent the national numbers or even outpace them. We will focus today on the metros that face housing values generally lower than national prices and the issues that creates.)

Budget of Buying “Adorable”, “Charming”, & “Cute”

If we zoom in even further, there is an interesting set of things that starts to happen for homes with values from $75k-$150k2. A quick Zillow search shows this price range makes up about 15% of the total listings in South Bend, Tuscaloosa, and Topeka and a study by the Urban Institute in 2020 showed 13% of all homes sales in 2020 were for under $100k, 50% of those bought by an owner-occupant.

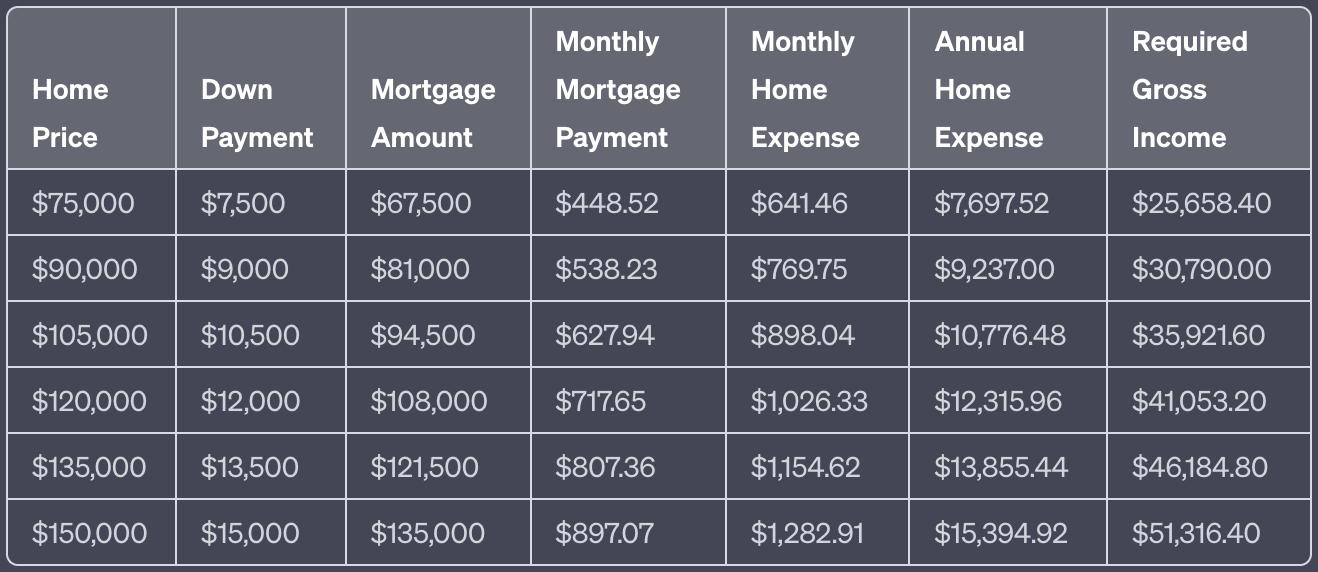

These homes are really affordable. If we make similar assumptions3 as made above, the the required household income to afford these homes makes them accessible to a range of people for whom homeownership might otherwise seems like a pipe dream.

Here is the kicker: not only are these homes affordable, they would also save people money versus renting. For example, rental rates for an equivalent space to a $75k-$100k home, range from $850 to $1,000 a month before accounting for utilities. Being able to buy these homes would save you money on your monthly budget while also allowing you to build equity.

This is wildly different than the math being done in larger cities. You can see below that the “Monthly Buy Costs” range from $3.5k to almost $6k in some of the larger US cities. If you’re working a service job in one of these places, good luck. But in a small city, if you diligently save for a downpayment and keep your credit in check, it feels like a real possibility to own.

Value of Ownership

Before we go any further, let’s back up for a second. Everything we’ve talked about thus far assumes that homeownership is clearly a good goal and pursuit. Many people, including those in expensive metros, may argue that renting makes a lot more sense. This can be true, but I think there is a lot missing from the conversation on the value of homeownership. The most common argument made is that homeownership is the most widely used tool for wealth building. While this can definitely be a good reason to pursue it, 2008 showed us that it can also destroy wealth. What are the other arguments for the value of homeownership?

Stability

If you’re able to attain a fixed rate mortgage, one of the values of homeownership is the stability it provides in housing costs. The payments are mostly stable, predictable, and you’re not at the whim of rental markets or inflation. You’re seeing this play out right now, as those who locked in interest rates of 2-3% a few years ago are protected against the inflation in mortgage rates and rental prices today. Volatility makes it hard to plan, especially when you’re living on a tight budget. The ability to forecast how housing plays into your monthly budget into the future can make things a lot easier.

Resilience

In addition to being able to predict your housing costs while paying down a mortgage, once you’ve paid it off, you have a level of resilience that is unmatched by renting. Just ask anyone who owned their home during the pandemic - even if everything went haywire and they lost their job, they could have comfort in knowing they had a place to live.

Home equity can also be a tool to leverage for making investments. Whether it is taking out money to start a business, invest in the home itself, or other future-facing investments, home equity is an enabler to take advantage of opportunities in addition to weathering shocks.

Transferability

Stability and resilience aren’t just benefits for the occupants - they extend out to their families, friends, and neighbors as well. While the homeowner is living, they can become a safety net when people in their networks fall on hard times. And when they pass, these benefits are transferred to the next generation. Entire neighborhoods are built on the stability and resilience that homeownership provides.

The wealth that can be created from an appreciation in home prices can be powerful. But even if this never happens - if the value never rises and you never sell - there are still a lot of benefits that can transform lives, communities, and cities.

The Current State

The story seems to be that homeownership is possible in these cities and that it has a lot of benefits. So what’s the rub?

The issue is that there is a difference between affordability and accessibility. Affordability is only as good as its accessibility. Many have heard the phrase, “It’s expensive to be poor.” A good example of this is Costco - sure you can buy bread at great unit prices, but because you can only get them by buying in bulk, those prices aren’t actually accessible to people with limited cash flow and tight budgets.

A similar dynamic appears at this edge of the housing market. When we say these homes are affordable, what we really mean is that they are affordable with financing. In other words, the monthly payments are affordable. But if someone had to buy the home outright with cash, this affordability vanishes. So to access the affordability, you first have access the financing - and that’s where things break down.

Many might think they know where I’m going here.

“Ah, yes. In order to access financing, people would need enough cash for a downpayment, have a good credit score, and have an acceptable debt-to-income ratio. That must be where this falls apart with these lower-middle income families.”

While these factors are certainly barriers to a lot of people, I’m talking about something different. There are plenty of people that have the cash for a downpayment, long stable rent histories, and good credit and even they cannot get a mortgage. Some might think that even so, these loans might just be riskier. But it's been shown that when people do get small dollar mortgages, they perform similarly to larger ones, and shouldn’t be treated as more risky.

The problem I’m talking about is actually on the supply side, not the demand side.

Mortgages: Percents Don’t Make Sense

How Mortgages (Typically) Work

Each year, 70-80% of homes in the US are bought with a mortgage. These mortgages are made either by mortgage divisions within banks, or by independent lenders that specialize in just making mortgages. In most cases, this is how it works:

A buyer decides they want to buy a home and make a formal offer on a house (usually after getting pre-approved at one or a few lenders)

The buyer then officially applies for a mortgage with a bank or another lender, handing over all sorts of information about their financials and the condition of the home

The lender approves the buyer for a loan equal to the appraised home price less the downpayment, and the buyer uses this money to purchase the home at closing

Soon after the home sale has closed, the lender usually then sells the mortgage to another investor on what’s termed the secondary market. Sometimes this is a government-sponsored entity (GSE) like Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, and sometimes it is directly to investors

Depending on the terms of that sale, the original lender may retain the rights to continue to service the loan (i.e., collect payments in exchange for a servicing fee) or the servicing rights transfers to someone entirely different

In order to bolster the mortgage industry, and thus homeownership, the government plays a big role in buying mortgages on this secondary market. In exchange for buying these loans and thus allowing the lenders to recycle money into more mortgages, they put in place standards on the quality of the loans. This is what is behind the terms “conforming”, “non-conforming”, “qualifying”, and “non-qualifying” mortgages.

In addition to standards for things like credit scores and debt-to-income ratios, there was legislation introduced by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) in 2011 that gave guidelines for being a “Qualified Mortgage”. These guidelines were not required to make mortgages, but they promise two things if followed:

Protection against legal action taken by a buyer claiming that a mortgage was made in a predatory way;

An increased likelihood that the GSEs would purchase them on the secondary market

There are multiple dimensions of the guidelines, but I want to call attention here to the fee caps. The CFPB introduced these guidelines to protect buyers from being charged high fees - trying to eliminate the temptation from originators to make the majority of their money from upfront fees and ignoring the quality of the loans. Here is the original fee schedule (note that these figures are indexed to inflation each year):

For a loan of $100,000 or more: 3% of the total loan amount or less.

For a loan of $60,000 to $100,000: $3,000 or less.

For a loan of $20,000 to $60,000: 5% of the total loan amount or less.

For a loan of $12,500 to $20,000: $1,000 or less.

For a loan of $12,500 or less: 8% of the total loan amount or less.

This is where it gets a bit complicated, so bear with me. Lenders are not required to stay under these caps. They can charge whatever they wish and the CFPB even says so: “Under the CFPB’s rules, only Qualified Mortgages have a limit on points and fees. Lenders are not required to make Qualified Mortgages, so they can charge higher points and fees if they choose.” But practically, the system has been designed such that they have a huge incentive to meet the guidelines. Between 80%-90% of all mortgages end up being sold to the secondary market, and of those approximately 70% are sold to the GSEs. Complying with the qualifying mortgage guidelines make it way more likely that these mortgages get purchased, in addition to the protections it provides from legal action.

Unit Economics of a Mortgage

Let’s review how the mortgage division at a bank or an independent mortgage company makes money on a mortgage. First, there are a few different revenue streams from making mortgages:

Origination fees: upfront, cash fees the bank charges at closing in exchange for creating the mortgage

Servicing fees: ongoing fees, usually charged monthly, for doing the work of collecting payments, tracking balances, and maintaining the mortgage

Interest income: the additional money you pay in interest on the principal outstanding, in exchange for having access to the money to buy the home (only applies if the bank holds onto the loan after it is made)

Gain on Sale: money made if the mortgage is sold to a third party on the secondary market (only applies if the bank sells the loan after it is made)

Then there is the cost side:

Origination costs: the costs associated with creating a mortgage - collecting and processing the relevant data, underwriting, guiding the buyer through the process, answering questions, software, compliance costs, and third party services

Servicing costs: processing payments, software to track payments and balances, and customer service

Cost of Capital: the cost of whatever capital source the bank is using to actually lend the money - this may be the costs of deposit accounts, a warehouse line of credit, or other financial arrangements

Below is a chart that shows how revenue may play out for loans in the range that we are discussing:

It’s not simple to understand if this revenue makes it profitable to make these loans because it’s much harder to get data on the cost side. But we can make some assumptions by looking at reports that the Mortgage Bankers Association puts out quarterly on industry averages. Here are figures from two recent releases, one reporting on 1Q 2022, and one reporting on all of 2022.

From the 1Q Report:

Total production revenue (fee income, net secondary marketing income and warehouse spread) decreased to 350 basis points in the first quarter, down from 353 basis points in the fourth quarter. On a per-loan basis, production revenues increased to $10,861 per loan in the first quarter, up from $10,569 per loan in the fourth quarter.

Average loan balance for first mortgages increased to a study-high $324,368 in the first quarter, up from $312,306 in the fourth quarter.

Total loan production expenses–commissions, compensation, occupancy, equipment and other production expenses and corporate allocations–increased to a study-high of $10,637 per loan in the first quarter, up from $9,470 per loan in the fourth quarter. From third quarter of 2008 to last quarter, loan production expenses have averaged $6,829 per loan.

Personnel expenses averaged $7,113 per loan in the first quarter, up from $6,438 per loan in the fourth quarter.

From the 2022 Annual Report:

The average loan balance for first mortgages reached a study-high of $323,780 in 2022, up from $298,324 in 2022. This is the largest single-year increase in the history of the report.

Total production revenues (fee income, net secondary marking income and warehouse spread) fell to 333 basis points in 2022, down from 382 basis points in 2021. On a per-loan basis, production revenues fell to $10,322 per loan in 2022, down from $11,003 per loan in 2021.

Total loan production expenses – commissions, compensation, occupancy, equipment, and other production expenses and corporate allocations – increased to $10,624 per loan in 2022, up from $8,664 in 2021.

Including all business lines, 53 percent of the firms in the study posted pre-tax net financial profits in 2022, down from 96 percent in 2021.

The takeaway here is that even at loan values above $300k, mortgage lenders are barely making money, if at all. After accounting for all revenue streams (excluding servicing revenue), they earn below 3.5% of the loan value in revenue, and production costs are at or above that level. These numbers only get worse as you get to loan values of $75k-$150k, because almost all of the income is loan value-dependent, and almost all of the costs are loan value-independent.

Percents Don’t Make Sense

When it comes to making mortgages on homes between $75k-$150k the math just doesn’t make sense for the banks - the homes are actually too affordable to finance.

Every way that the lender makes money is based on the value of the loan. The origination fees are capped by a percentage of loan value and Gain on Sale is influenced by interest rates, which are tied to loan value. But almost every way that a lender spends money to originate a mortgage is independent of the loan value. The only cost that is tied to the value is the sales commission (usually 0.5-1% of the loan value). But as we saw in the hypothetical scenario at the beginning of this post, even this cost is problematic. At these lower home values, these commissions are small in actual dollars, incentivizing salespeople to spend time upmarket.

The Urban Institute, Pew Research, Local Housing Solutions (NYU), the Fed, New America, and others have profiled this issue and the data bears the math out. For homes under $150k, only approximately 26% get purchased with a mortgage, compared with over 70% for homes above $150k. Not only are they less likely, they are also getting scarcer (see below). Some of the decline in availability is due to general price appreciation, but not all, meaning they are both hard to get and getting harder to get.

There are people (Urban Institute, for example) working on making these mortgages more available, but almost entirely from a policy and/or non-profit perspective, through organizations like Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs). While these efforts are important, they have been slow to address the problem and also proven difficult to scale.

The experience of Fahe and the MicroMortgage Marketplace demonstration reveals that even with concrete steps taken to concentrate resources for small mortgage financing and address lending barriers, there are still major challenges to reaching borrowers and homebuyers. Some of these are baked into industry structure, such as compensation models, but others might be even harder to solve, such as property condition.

Urban Institute, MicroMortgage Marketplace Pilot

Seller Financing or Cash Now

If mortgages are scarce, then how do homes get purchased? There are two ways that people buy homes if the mortgage route doesn’t work out: seller financing and cash.

The latter is probably easy to understand as an option. If I can’t get a mortgage, I can just choose to pay all cash to the seller. Except obviously that requires you to have tens of thousands of dollars or more, making it possible but not probable for the people whose homeownership dreams rely on buying in this part of the market.

The seller financing solution exists, but is opaque. In these arrangements, the seller essentially “lends” you the money for the home by spreading the purchase of the home over time. This can be great for the buyers if done well, but can get predatory quickly if not. Most of these deals happen between private parties, and usually between real estate investors and individuals. One story we’ve heard of how this can go wrong is that an owner advertises a “lease-to-own” contract on a home. The buyer would essentially rent the home for 3-5 years, and then at the end have an option to buy it, either for cash or with a mortgage if they can get one. This is generally a bit more expensive than renting, but is valuable because of the option to buy. However, these agreements can be written very broadly, giving the seller wide latitude to break the contract, sometimes mere months before the buyer is owed the option to buy. They evict the potential buyer for “breaking” the contract, and do the whole thing over again. It seems a long way to go for the rent premium that you can charge, but nonetheless, this is the kind of thing that can happen in such a unregulated and opaque market.

The other problem with seller financing is its scalability. The mortgage market works at such a large scale because of the secondary market. This allows originators to recycle cash into more mortgages, without having to wait for them to be paid down. With seller financing, even when done equitably and well, the original investors have money tied up for a while before they are able to repeat the process with new buyers.

Hurry Home

This problem isn’t new to us, and in fact, we helped start a company in 2017 that attempted to address it called Hurry Home. You can see more about how their model worked here. The founders, Jada McClean and John Gibbons, did an amazing job understanding the problem (a lot of what I’ve learned comes from them!) and in executing early on. They were accepted into TechStars Chicago accelerator, became part of Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation Labs’s inaugural Housing Lab, and piloted with help from the City of South Bend, actually getting some South Bend residents into homes.

They ended up shutting the company down a few years later, but not for lack of understanding the problem. Turns out, it’s just a really hard problem to solve and to scale. But nonetheless, with those lessons in hand, we still believe there are ways to address this problem that can work.

The Opportunities

If the studies are correct, there are hundreds of thousands of properties every year that fit into the $75k-$150k range. And even if prices rise, the mechanisms remain - it will probably always be harder to get a mortgage at the low end of the market.

From a Urban Institute survey in 2020, they found roughly 300,000 properties sold for less than $100k by owner-occupants. If we adjust that number slightly to look at properties under $150k, we could be talking about 400,000-500,000 properties annually. At $3k-$4k in revenue potential per property, this is a $1.5B-$2B market. This may be a small percentage of the overall mortgage industry, but as a startup opportunity, it makes sense to pursue.

There are three obvious paths forward, and probably more non-obvious ones.

Cut The Costs

One way to think about this is to say, ‘what would have to be true for mortgages at this price point to be profitable?’ If you do the math, and assume a bank’s total revenue is at 3.5% of loan value and it wants to see a 1% net return on the origination and sale of a mortgage, it would look something like this:

Going back to the total production costs cited by MBA, we would have to find a way to cut costs by 70%-80% to make these loans viable, going from over $10k in costs to closer to $2k-$3k. There would need to be a lot more research into the cost structure of origination and underwriting, but one path would be to get a more detailed idea of where the bulk of that cost structure lies and try to find new and cheaper ways to do it.

The beauty strategically of this route would be that if you find a way to cut costs for these loans by 70%-80%, there is an advantage in going upmarket as well. The mechanism that is currently working against the model, fixed costs no matter the loan size, would start to work for you, allowing you to offer either lower fees or to take a higher margin on larger loans.

Throw the Mortgage Out

Another path would be to question if the mortgage is even the right tool at this edge of the market. For most of human history, housing has not relied on the mortgage system that the US has today. Even globally, the way we finance housing is unusual. So who is to say that houses under $150k should work the same as those above $300k?

There are probably a lot of paths to pursue here. Hurry Home looked at innovating on the seller-financing system. I’m sure there are other ways to do that specifically, as well as other models that might work as well. There are plenty of rabbit holes to pursue, such as learning how the rest of the world finances low-value homes.

Secondaries for Seller Financing

As we discussed, seller financing, even if done well quickly runs into a scaling problem because of the inability to quickly and predictable sell the loans and recycle capital back into the market. If there was a way to make a more formal and liquid secondary market, perhaps there would be a way to scale some of the seller financing that does already work. The secondary market could also force some quality standards on the seller financing market, as more sophisticated investors would look for contracts they can trust.

Innovation at the Edges

Innovation in housing is not a foreign concept in these places. Land banks, co-ops, and other solutions have a long history in these cities. Stories like that of Better Homes of South Bend show a path toward improving access to housing amongst seemingly insurmountable odds.

I also don’t think innovation that works in this end of the market will stay confined to it. As mentioned, if you were to be able to cut the costs of origination, it has applicability across the housing market. But even when looking specifically at affordable housing, as people continue to innovate on things like materials and building techniques, there could be an increasing demand for innovation in financing. Say someone hits the holy grail of bringing home building costs down - cutting the average new build in a place like South Bend from $250k to $100k - what happens then? If the mortgage system doesn’t adapt, the same mechanisms here could still play out, again reinforcing that affordability isn’t enough - that affordability has to be accessible.

Housing affordability is an issue capturing more and more national attention. Homeownership has been a public policy goal for nearly 100 years now. The Great Depression pushed the housing finance system to the brink, allowing FDR to introduce an entire new set of actors and policies that transformed the mortgage system into what the US depends on today. Trillions of dollars of mortgages are originated each year and for most Americans, it is the biggest purchase of their life. With skyrocketing prices, mostly in large metros and expanding suburbs, this goal feels out of reach to many.

The system has become very complicated, especially in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Combine its complexity and its size and you are bound to get weird, unexpected, and unintended outcomes on the edges of the market. The system works generally, for the majority of people in a majority of situations. But at the edges, the system sometimes works contrary to its goals.

Known for their affordability, small city housing markets are usually looked at with envy by those in big cities. For the most part, this is true. But oddly enough, affordability can also be a curse. When housing gets too affordable, the mortgage system and its economic incentives break down and people with lower-middle incomes struggle to take advantage of the affordability that everyone else covets.

It’s in these cities, touted for their affordability, that we believe there is an opportunity to offer teachers, nurses, public servants, and service workers access to homeownership and the all of the benefits that come with it.

If you’re interested in solving this problem, or already are, please reach out at dustin@invanti.co - I’d love to talk to you.

Works Cited:

Median Home Prices by Year, St. Louis Fed

Median Listing Price Versus the United States in South Bend-Mishawaka, IN-MI, St. Louis Fed

Median Listing Price Versus the United States in Tuscaloosa, AL, St. Louis Fed

Median Listing Price Versus the United States in Topeka, KS, St. Louis Fed

Improving the Availability of Small Mortgage Loans, Urban Institute

Listing for 821 E Victoria St, South Bend, IN 46614, Zillow

Listing for 821 S Camden St, South Bend, IN 46619, Zillow

Listing for 267 Maple St, South Bend, IN 46601, Zillow

Listing for 1046 N Elmer St, South Bend, IN 46628, Zillow

Listing for 1 bed, 1 bath apartment at Riverside North Apartments, apartments.com

Listing for 1 bed, 1 bath apartment at 710 E Colfax Ave, # A, South Bend, IN 46617, Zillow

December ‘22 Rental Report: Despite Rent Growth, Renting a Starter Home is More Affordable than Buying, Realtor.com

Small-Dollar Mortgages: A Loan Performance Analysis, Urban Institute

Highlights From the Profile of Home Buyers and Sellers, National Association of Realtors

What is a Qualified Mortgage?, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

My lender says it can't lend to me because of a limit on points and fees on loans. Is this true?, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

FHFA Report to Congress 2019, FHFA

MBA: 1Q IMB Production Profits Decrease (2022), Mortgage Brokers Association

MBA: 2022 IMB Production Profits Fall to Series Low, Mortgage Brokers Association

Cost to Originate Study: How Digital Offerings Impact Loan Production Costs, Freddie Mac

Small Mortgages Are Too Hard to Get, Pew Charitable Trusts

The MicroMortgage Marketplace Demonstration Project, Urban Institute

Millions of Americans Have Used Risky Financing Arrangements to Buy Homes, Pew Charitable Trusts

Small balance home mortgages, Local Housing Solutions (NYU)

Better Homes of South Bend, Gabrielle Robinson

Works used in Research:

Housing Finance at a Glance - A Monthly Chartbook January 2022, Urban Institute

Trends in Mortgage Origination and Servicing: Nonbanks in the Post-Crisis Period, FDIC Quarterly

Small Dollar Mortgages Can Increase Affordable Housing, St. Louis Fed

Small-Dollar Mortgage Lending in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware, Philadelphia Fed

Small-Dollar Mortgages Offer Much-Needed Entry into Homeownership, Cleveland Fed

Small Mortgages are Hard to Get Even when Prices are Low, Pew Charitable Trusts

The Lending Hole at the Bottom of the Homeownership Market, New America

Making FHA Small Dollar Mortgages More Accessible Could Make Homeownership More Equitable, Urban Institute

Most assumptions here will be based on: 30-year mortgage, 7% interest rate, 10% downpayment, 1.25% of the home price for property tax and insurance, 1% of the home price for maintenance, and PMI of 0.5% of the loan amount until 20% equity is reached, and a 30% gross income limit on total housing spend

There are homes that even exist below $75k, but these are also the most likely to have issues that require significant repairs. We will cover how these homes have their own set of issues in a future profile.

Assumptions: 30-year mortgage, 7% interest rate, 10% downpayment, 1.25% of the home price for property tax and insurance, 1% of the home price for maintenance, and PMI of 0.5% of the loan amount until 20% equity is reached, and a 30% of gross income limit on total housing spend